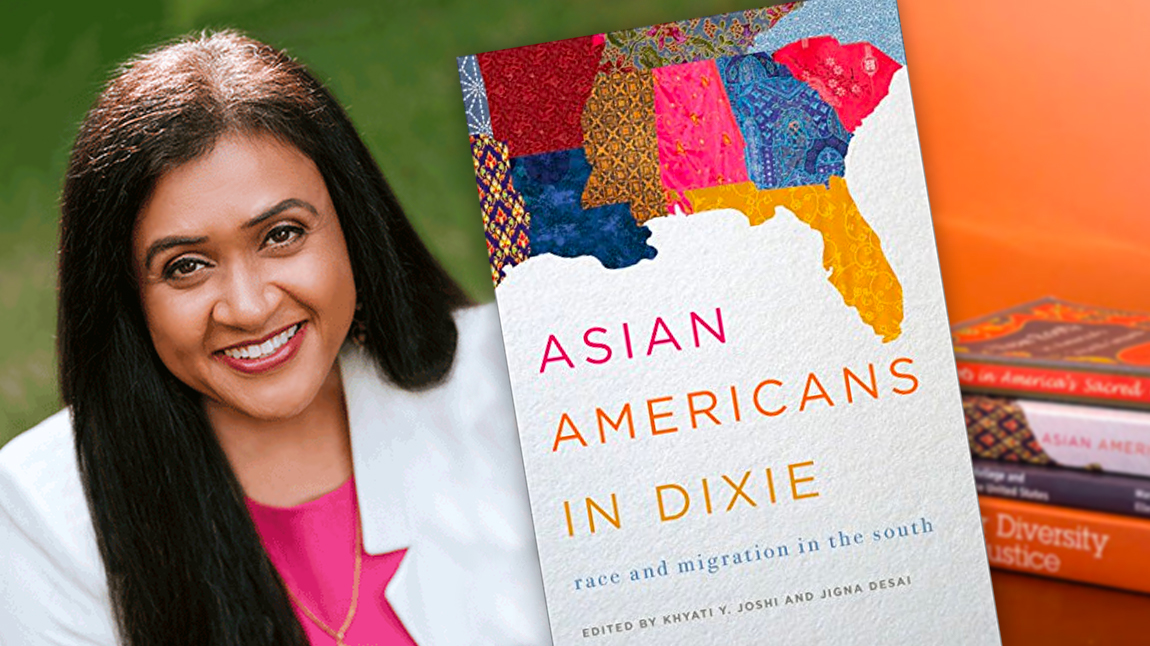

In the hand pie episode of “Somewhere South,” Vivian meets food scholar and author Sandra Gutierrez for lunch at Sarah’s Empanadas in Durham, N.C. Over classic empanadas and new 'Southern-Latino' versions, Gutierrez details the historic journey of the hand pie from the Middle East to the Americas. Her knowledge of the hand pie is rooted in years of research and lived experience. As Vivian mentions on the show, “she literally wrote the book.”

“Empanadas: the Hand-Held Pies of Latin America” is Gutierrez’s third cookbook. Gutierrez’s first book, “The New Southern-Latino Table” was a groundbreaking contribution to helping define the beginning of a shift in Southern and Latino foodways. In 2019, Gutierrez’s work became part of the permanent FOOD exhibit at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, read about her contributions to American foodways in the exhibit’s official essay, “The Migrant’s Table,” and see some of her cooking objects, right next to the replica of Julia Child’s kitchen!

Gutierrez also serves on the series’ advisory board. We caught up with her to learn more about the humble hand pie and the evolution of Southern-Latino food.

You’ve written so many books! What inspired you to take on empanadas as a subject?

I wanted to tackle the complete scope of the 21 Latin American cuisines in one single subject to compare how the food of each country differs. My mission has always been to break stereotypes—those that surround Latin American people, but also those that have boxed our multicultural food into a single category. Everyone who first thinks of Latin food, thinks "tacos." Although those are absolutely delicious, there is so much more.

Hand-held pies are versatile and have lately become very popular in this country; however, both in the Southern region of the U.S. where I live and throughout Latin America, the story of the hand pie can be traced back to ancient culinary traditions that came from "someplace else" but that we made our own. “Empanadas: the Hand-Held Pies of Latin America” came out of that desire to explain the origin of one single food that has gone through myriad transformations as each country put their own stamp on it.

The breadth of research for this one required reaching far back into history. How did you narrow your focus?

As a food historian, I am always looking for the origins of ingredients, recipes, and culinary techniques. The history of empanadas has a very clear path that is easy to trace back to Persia. Once I found those first recipes and the very first depictions of hand-held pies in ancient Persia (today's Iran), it became only a matter of following it forward, through the spread of the Ottoman Empire in Europe, and then the European expansion into the Americas. History leaves culinary imprints that remain as answers we find centuries later. This is why food is so important, because when we're blessed not to need food only for survival — when we can actually study it and investigate its origin, path of distribution, journeys around the world, etc. — we get anthropological, socio-political and historical knowledge that explains so much about humankind.

Was there anything interesting you learned that didn’t make it into the book?

What I wish I could have written more about is all of the modern variations of empanadas that can be made today, not only within the Latin American territories, but around the world. The empanada hasn't ever remained static. The fillings, the dough and the spices that season them are always in flux, and these all paint a picture of humanity in the present.

In our hand pie episode, you share what you know about how the Persians first made this hand-held food. Can you elaborate on why it was so important that it was portable?

The Persians were building an empire; soldiers needed food that was portable but also durable. The first empanadas allowed for the fillings—mostly meats mixed with fruits—to stay edible for days. Many of the original dough used to encase the fillings were heavily salted, which helped to preserve the meat inside; other encasements could be quickly made, without leavening, and carried away for journeying or battles. It is no surprise that empanadas remain portable food. That's one of the reasons the hand-held pie became so central for miners, whether in Scotland, or in Virginia--they could take their hand held pies into the mines. In Latin America, they became the food for workers and school children alike.

Let’s talk masa! Doughs in Latin America vary greatly. What are some types of dough used in empanadas that people may not know about?

In Spanish, "masa" means dough—any kind, not only the one made with nixtamalized corn. Empanada means "encased in bread," but the dough can be made of many ingredients that are not just based on wheat. Everyone thinks that gluten-free dough is a new thing, but Latin Americans have been making it for centuries. I offer 10 different types of dough in my book, but my favorites to showcase are those made entirely of either yuca root (a tuber similar to a long potato, but starchier, that grows underground), or those made of plantains. These don't have any flour added; one ingredient, boiled and mashed, becomes an encasement that gets crispy when cooked. I also feature wheat-based empanada dough, because that's what we inherited from the Persians. However, in Argentina, instead of making pastry with cold ingredients, it’s made with boiling, hot water. The result is pastry that cooks like crusty, Italian bread. I find it extremely important to break stereotypes in every single aspect of cooking. Empanadas, allowed me to showcase different dough, plus sweet fillings, savory fillings, sweet and savory fillings, and even savory pies that are covered in sugar before serving.

Explain how demographics have shifted in the U.S. South as it relates to the history of Latino migration.

The first Mexican migrant workers arrived to the South in the 1880’s, but for the most part, until 1990, the South remained hermetically sealed to widespread Latino immigration. Of course, through the 20th century, Florida was the exception because of the arrival of Cuban exiles in the 1950’s. Mass Latin immigration to the South resulted from the repeal of the Temporary Protective Status (which precluded the deportation of immigrants back to their countries due to natural disasters or armed conflict), and to the legalization of certain work status passed by government legislation, among other factors. According to the US Census Bureau, the number of Central Americans alone grew nine-fold between 1980 and 2013. In the 1990's highly skilled South Americans faced flailing economies in their countries and sought job opportunities in the United States. The professions of Latinos in the South vary, from agricultural workers, construction laborers, scientists, software engineers, university professors, and doctors. From 2000-2010, the Latino population in the South grew by almost 70 percent to more than 2.3 million people; in Georgia, it nearly doubled, and in states like Mississippi and Alabama, it more than doubled. Mexicans, Colombians, Cubans, Guatemalans, Puerto Ricans, Hondurans, Salvadorans and Dominican Latinos make up the largest population shifts. According to The Washington Post, in Texas alone, the percentage of Latino population will grow from 38 percent in 2010 to 53 percent by 2040.

And this has of course shaped foodways in the region. You view food scholarship through a particular lens of Southern-Latino, which is a term you coined years ago. Tell us more about what this means.

Soon after arriving to live in the South in 1996, I became the first Latina food editor of a newspaper in North Carolina. We were the first Latinos in our neighborhood and this fact was very noticeable.

I also started noticing a new culinary movement developing in our region. Chipotle peppers were making their way into barbecue sauces and jalapeños were peppering hushpuppies. Friends were filling tacos with brisket, and serving them with chimichurri. Others were making tamales with cornmeal and topping them with shrimp and pineapple salsas; or smothering biscuits and pound cakes with dulce de leche. I knew we were onto something.

By the time the University of North Carolina Press asked me to write a book in 2009, what I called the “New Southern-Latino Movement” was impossible for anyone to ignore. People were growing their Southern roots by not denying them, exposing the new racial and sociopolitical realities of an entire region one dish at a time. The next year, Southern Foodways Alliance dedicated an entire conference to the Global South, which included the Latin American influences on Southern regional cuisine.

What I had discovered more than a decade before was an organic movement in which Latino and Southern home cooks found themselves in the same territory, with similar cooking techniques, ingredients, and cultural culinary bases. They adapted and created recipes that married their two cultures. By living here, I— both of the American South and from Latin America— was able to taste it in other people’s homes before I named it. My Latino friends were substituting grits for nixtamalized corn flour and replacing traditional chipilines with collard greens. My white friends were serving unforgettable menus featuring cabrito en barbacoa with tostones and coleslaw. My own children were eating field pea ceviches and Cochinita Pibil Carolina sandwiches, topped with coleslaw. Here was a revolution created by regular folks seeking to find common ground through food.

As a Nueva Sureña, I am not the creator of this culinary movement; I am simply the food-loving historian who was in the right place at the right time to witness and record its birth. I think that being part of and open to both cultures, without prejudice, allowed me to see what many had ignored before me. My prediction is that the New Southern-Latino Movement will continue to grow. We’ve only seen the beginning.