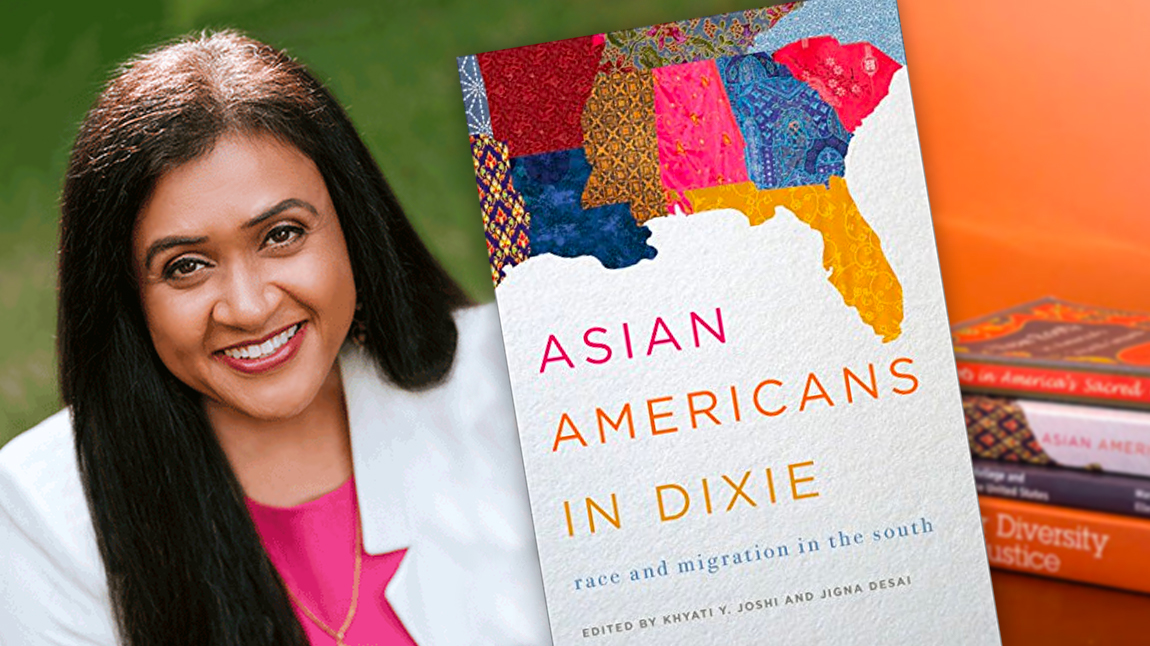

Khyati Joshi is a social scientist and education scholar at Fairleigh Dickinson University in Teaneck, N.J. She is the co-editor of “Asian Americans in Dixie: Race and Migration in the South,” which was a helpful resource for our producers in preparation for the greens and pickles episodes. Joshi has a new book coming out in July from New York University press: “White Christian Privilege: The Illusion of Religious Equality in America.” We chatted with her about how and why Asian Americans are left out of the narrative of the American South.

Q: Why do you think Asian Americans are overlooked in the story of the American South?

A: For me, this always goes back to what we're taught and we are never taught that there is actually anybody else in the South beyond Black and white. Right? Of course that story is also limited because actually all we ever learned is slavery happened. There's no question that the enslavement of Africans and the legacy that's had on that part of the country is huge but it's been a huge disservice to all of America in terms of the way the South gets depicted.

Q: We were really struggling with that in the pre-production conversations. How can we challenge this Black-white binary that is entrenched in the narrative of the American South?

A: I'm so grateful to my colleagues who are historians who are excavating the history literally day by day. I never learned about the Filipinos who came in through New Orleans in the 18th Century. I never learned about that until probably 10 years ago well past when I actually considered myself a scholar in Asian American studies. It's the stories that we don't know, like Vivek Bald’s work on the Bengali peddlers is just huge. It's so critical to understanding that this network of Bengali men were here... Those stories — we don't know them — are being excavated literally, as we speak.

Q: There is a tendency to portray the South as this non-cosmopolitan, non-modern, backward place. How does that contribute to the narrative that excludes these folks from our understanding of the American South?

A: I think that also goes back to the way the South has been depicted. If the South is only seen as Black and white and all we ever know is slavery and the burning of Atlanta and stuff like that, then nobody else exists. Granted the numbers were quite small but you did have these Asian communities. I think the racial legacy and what has happened even through the 20th century is predominantly discussed via slavery, segregation and desegregation. And so instead of teaching history chronologically, going thematically could make a difference. So one of the things that I think about is the issue of citizenship. If you look at who was allowed to be a citizen and who wasn't, we're expanding the conversation. There’s Dred Scott. There’s Ozawa. There's all the Syrian and Armenians cases. There's all these people who tried to become citizens and they couldn't. The other thing about the history of the South is while it's been about Black and white, let's be clear, it's been about Black and how that Black doesn't fit into whiteness. If we can actually make it about whiteness and look at the way that public policy supported white supremacy then it will also tell us a different story. We had Vietnamese fishermen in Texas and they faced hostility. It's why the Southern Poverty Law Center had to file suit against the Ku Klux Klan.Those stories don't get picked up because they're also not the narrative. It is very difficult whether you're a scholar or journalist to change this narrative. It takes a long time.

Q: You just mentioned something that people may be surprised to learn about Asian migration in the American South: the Filipinos in New Orleans.

A: In the 18th Century, Filipino men came through New Orleans. It is another point of entry for Asian Americans. It’s not just the Chinese and the Asians coming to the West Coast. It's also the way that the various stories get framed. If more people knew about the Chinese in Mississippi, if more people knew about the Chinese in Arkansas in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, people would think differently about the American South. That doesn’t happen unless the data is collected or a scholar writes about it. I’m specifically remembering Leslie Bow's parents. Leslie Bow wrote the book, “Partly Colored: Asian Americans and Racial Anomaly in the Segregated South,” and her essay in our anthology, “Asian Americans in Dixie: Race and Migration in the South.” In her introduction, she talks about her mother not being able to go to this school dance in high school because her parents both grew up in the 1940s in Arkansas. They're both Chinese. Now imagine if these kinds of stories could get out, how you would look at the world differently, how you might look at the South differently. I also think that right now people don't see it as cosmopolitan because look at what's happening today. What's the story about the South today? The stories about the Confederate monuments, right? Guess what? We've got problems with statues everwhere - in New Jersey and New York too. Just the other day, I was reminded about this one doctor statue in New York City. He was considered the father of gynecology and the fact is that he performed experiments on slave women because he believed that they felt no pain. This statue is in cosmopolitan New York City.

Q: It struck us while working on “Somewhere South” that it's never just an immigration story, it’s a labor story. How were these Asian immigrants who came here to do specific jobs viewed?

A: My response to that would be very complicated but let's think about after 1965. The University of Alabama at Birmingham has one of the most preeminent hospitals in the United States. A lot of Indian physicians ended up there because of the Immigration Act of 1965. We don't think about a place in the South as being a preeminent location for medical research but it's there. What would be interesting is if somebody actually collected data on discrimination and the kind of discrimination those doctors face. We know it from anecdotal stories but because of their class status, because immigrants usually don't want to cause a ruckus, they keep to themselves. Things happen. Things never got officially reported. It is not reported because of their own internalized racism, their own internalized colonialism, the notion that: ‘Well, I'm a visitor here.’ You have a lot of new immigrants coming in the 1990s and 2000s to work in a variety of industries. The people with H1B visas are so dependent on their employer to be in this country. You think they're going to report racial or religious discrimination?

I'm a product of the Immigration Act of ‘65. My dad is a doctor and came here because of that. While we know that all these very intelligent people came over, we actually don't know a whole lot about what happened to them. When I think about my father's experience and so many of his generation, they faced discrimination. For the majority, it wasn't life threatening but they also weren't speaking up. Some of the stories I know are not even from my dad, it's from his office manager. My dad hired this woman in 1976 when he first opened up his own practice. He’s an OBGYN. She worked with him until he retired. She was a Southern Baptist, a white woman who faced hostility from her church for working for my dad. She defended my dad like you would not believe, but the church was very unhappy that she was working for this dark heathen man. It wasn’t only that he was dark, it’s also he wasn't Christian. He didn't have Hindu written across the forehead, but you know racialization of religion. He’s the other… Patients would say to him: ‘Dr. Joshi, you're not one of them.’ But here's the story that doesn't get told: this happened five years ago to a friend of mine who is a cardiologist in New Jersey. A man was brought to the hospital and his grown children did not want my friend, who is a South Indian physician, working on their dad. The nurses are like, ‘He's the head of the department of cardiology. He’s your best guy.’ ‘No, we don't want him’ — at three o'clock in the morning. So again it’s about what stories get told.