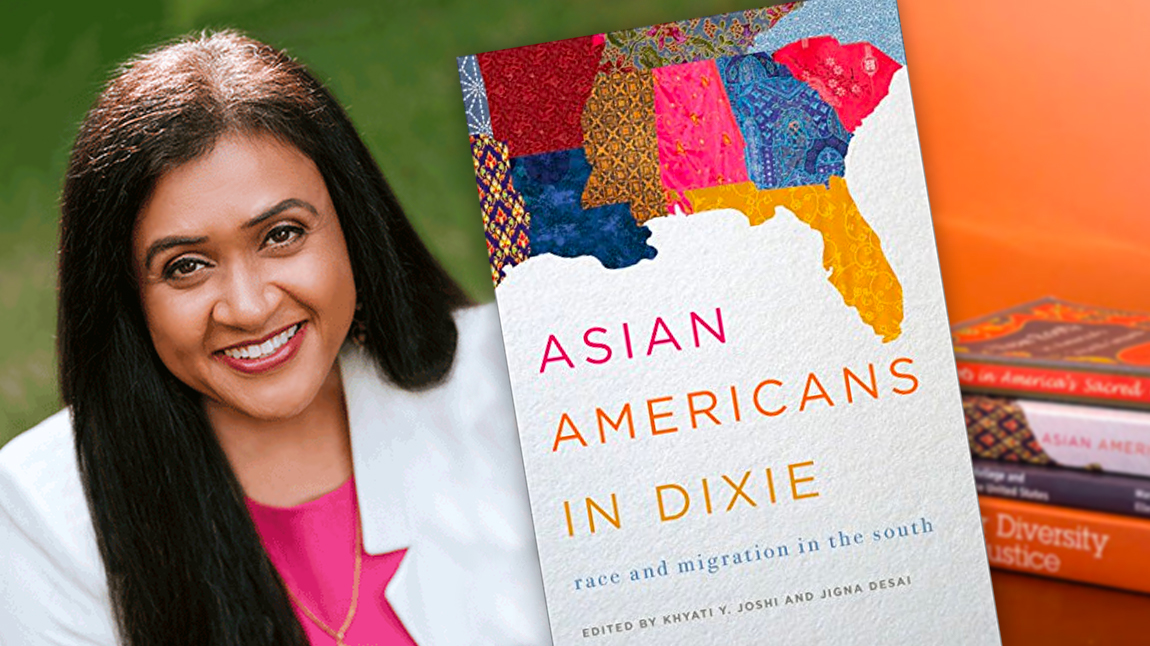

One of the scholars who has been advising “Somewhere South” is Simi Kang, a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, Pa. Her deep knowledge as an ethnographer has shaped how we share these communities’ stories, especially in the “What a Pickle” episode and next week’s “It’s a Greens Thing” episode.

Kang’s research focuses on Asian American communities in the American South deeply integral to the food industry. She’s spent time with the Vietnamese- and Cambodian-American fisherfolk in and around New Orleans and the Gulf Coast. She works as a grant writer and advocate for Coastal Communities Consulting, a nonprofit that serves southeast Louisiana’s commercial fisherfolk and their families. Kang has written about these communities in Gravy, a publication of the Southern Foodways Alliance, in an article titled: “An Industry's Heartbeat: Louisiana’s Southeast Asian American fisherwomen foster a way of life.” In Hyphen, a nonprofit news and culture magazine that tells the stories of Asian America, Kang wrote about a farming cooperative in the Vietnamese community in New Orleans: “Feeding Versailles: The Versailles Vietnamese American community responds to and rebuilds in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and the BP oil spill.” With those stories in mind, we asked her a few questions.

What sparked your interest in these communities in New Orleans and the Gulf Coast?

I'm from Minneapolis. As a young person, I didn't really have a clear sense of my own identity as an Indian American. It took finding a community of Asian American activists and organizers, many of whom were Southeast Asian American. Those folks became my chosen family. A few of those friends had gone to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina to help rebuild the Vietnamese American community. So that's how I first learned about the community. I decided that South Louisiana would be a great place to be thinking critically about labor, race and immigration issues in Southeast Asian American communities. So I transitioned my work down there.

How did these folks come to that area and become involved in the fishing industry? Were they involved in the fishing industry in Vietnam?

Each family's story is different. A lot of the first wave of refugees who were brought to the United States after the U.S. engagement in Vietnam between 1975 and the late 1970s usually were more resourced than people who came after them. So they hadn't necessarily been working in commercial fishing or other food industries but had other kinds of income in Vietnam. This is what folks have told me: when they got to Louisiana, commercial fishing was a place where they didn't necessarily need to know English. So people started working on existing boats captained by white Louisianians, African-American Louisianians, etc. It was paid day labor. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, commercial fishing was a pretty good business. You could make a decent amount of money on a two- or three-day trip. People were able to save a fair amount and subsequently buy their own boats. And then fishing became central to the economy of the Vietnamese American community. Then folks who came later and did have fishing knowledge had a leg up because people already in the industry could give them loans to buy their own boats. Over time, it just became really important to the community. It's also worth noting that it wasn't just men working on the boats. Women were working shifts as seafood processors, shucking oysters and deheading shrimp. In many homes, both parents were working in seafood in some way.

Were there particular challenges that these communities faced in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005?

When the Vietnamese refugees were resettled in New Orleans, they were actually brought there by the Catholic church. In 1975, everybody was put in one housing complex in New Orleans East called Versailles Arms. Folks created a community around that area. It is physically isolated from New Orleans proper and so people had to become self sufficient because they weren't really receiving resources. So New Orleans East wasn't hit as hard by Hurricane Katrina as other spots of the city, but it was a part of the 85 percent of the city that was underwater. Their homes in New Orleans East needed repair and then their boats were also completely in disrepair down at the docks, which are sometimes 2 ½ hours away. There were no resources to fix both. A lot of people just never went back to commercial shrimping or commercial fishing after that. Then in the months that followed Hurricane Katrina, the mayor at the time zoned a spot just two miles down the road from the New Orleans East community to put all of the Katrina waste. They put a landfill basically in the community's backyard. It’s highly toxic. It's not what you want anywhere near where your kids breathe, let alone in your groundwater or especially for this community when people are growing kitchen gardens in almost every backyard. That move was accurately identified as an act of environmental racism. There's actually an excellent documentary called “A Village called Versailles” that was made about the community's response to this landfill.

Five years later, those folks who survived Katrina to continue working in commercial fishing were affected by the BP oil spill. What happened?

BP happened a few days into one of the two shrimp seasons that the folks I work with rely on for their annual income. So they had to get out of the water and they lost 50 percent of their income. Then the subsequent season some of them still couldn't go out because they were in so much debt that they effectively lost a full year of income. Folks had to go on unemployment and get food stamps, which was a particularly difficult process in some cases because of language barriers.

You talked about how women often worked in the seafood processing but one of your stories really goes into how these women are integral business partners with their husbands who were often working on the boats. Can you talk a little bit about their role, especially in the aftermaths of these two events?

It's worth mentioning that these women aren't just doing the care labor in the home, they are usually working at least one job and they are acutely knowledgeable about commercial fishing. They can get on the boats and help their family members who own the boats. They're almost always the people who deal with the finances of the business. I found the women in these communities really have their hand in every area of their families’ lives — economic life, cultural life, communal life. It's really the women who mobilize the industry.

When I was living in New Orleans, Baton Rouge flooded pretty badly in 2016 and there's a big Southeast Asian community there as well. My boss, who is knowledgeable about disaster relief, said: ‘We need to get people food.’ A bunch of fishermen contributed a percentage of their income for that month and we raised several thousand dollars in a few hours. My boss used that money to buy bags of rice, fish sauce, ramen and other culturally-appropriate staple foods because the food banks didn't have things that the community needed to feed their families. We got all of that to Baton Rouge and then the people who showed up to distribute it were the mothers, the sisters, the aunts. They're really doing the labor of keeping the community together, especially after a disaster.

You wrote about the VEGGI Farmers Cooperative in New Orleans East. It sounds like there was already this base of gardening knowledge within the community. Is that true?

I remember my boss telling me that there was a constant search for space to grow food at the housing development in New Orleans East. That wasn't a part of the thought process when Vietnamese refugees were resettled there. Nobody thought these people will need to grow food. So aunties were making their own gardens under stairwells and finding other ways to grow food. As people started having homes and lawns, they were more able to kind of supplement what they could find at the grocery store.

What led to the farmers’ cooperative?

There were so many elders who were left economically stranded after the BP oil spill. Two young men, Daniel Nguyen and Khai Nguyen, went to Mary Queen of Viet Nam, the Catholic church in the community, and said, ‘We need a grant to start teaching the elders who are now off the water how to grow food economically.’ It was really founded as a safe place for folks who had to get off the water after BP. They had to do a lot of experimentation to figure out how to grow at enough scale where people could earn paychecks. What they found was that the farm ended up serving two purposes. The primary income was from non-Asian restaurants in New Orleans that needed really good salad greens and local vegetables. And then the local corner stores as well as the farmers’ friends and family were asking for particular kinds of culturally appropriate vegetables and Vietnamese herbs.

How is the COVID-19 pandemic affecting these fisherfolk?

Under COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders and given how fraught the restaurant economy is, commercial fisherfolk can't sell anything they catch right now. This is another big disaster happening just at the beginning of a shrimping season, and Coastal Communities Consulting is prioritizing getting everyone enrolled in unemployment and helping fishers get access to Small Business Association disaster funding.

While our community of food producers is unable to do their jobs, as I said before, many of them cultivate gardens at home. One fisherman we have worked with for years grows all of the produce you can think of in a lot next to his house, including squash and greens, potatoes, eggplant, okra, herbs, and citrus trees. He is well known in his community in Buras, La. for giving away food. My boss spoke to him the other day about how he is using his garden. He said that he tends his garden every day and leaves cut produce out for his community. He isn't interested in selling what he grows elsewhere or charging anyone for food. He just wants his neighbors to feel like they can care for themselves and their families in such uncertain times.