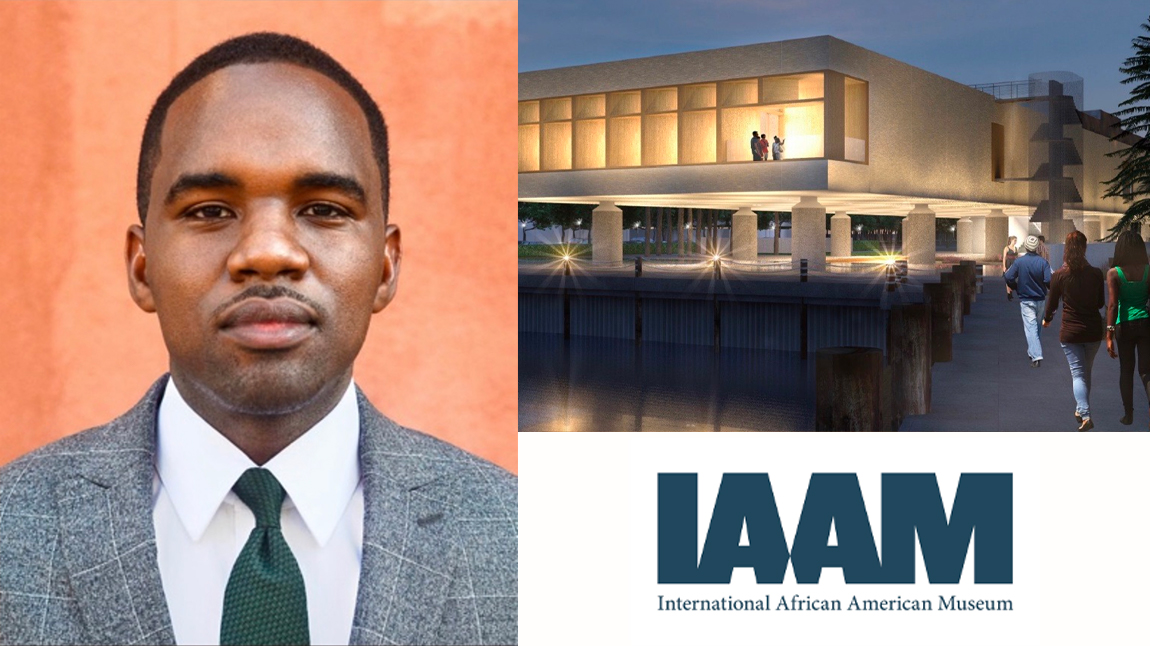

The International African American Museum (IAAM) is a museum of African-American history being built in Charleston, S.C., on the site where Gadsden's Wharf, the disembarkation point of up to 40 percent of all American slaves, once stood. Construction of the IAAM began in January of 2020 after 20 years of planning. In 2018, Elijah Heyward III joined IAAM as its chief operating officer. We spoke with Heyward about our experience filming segments of our porridge episode in Charleston and on Edisto Island, South Carolina’s role in memorializing the transatlantic slave trade, and his take on soul food.

Can you tell us a little bit about who you are and how you ended up as Chief Operating Officer of International African American Museum (IAAM)?

I have been enamored with history for most of my life. I grew up in Beaufort, S.C. and spent many of my summers in Charleston. My parents were very active in our community, namely as volunteers at Penn Center, the site of the former Penn School. The Penn School was one of the country's first schools for the formerly enslaved. The grounds captivated me as a child and served as a place where we gathered for events like “Community Sing” and the annual Heritage Days programming. Penn Center was one of the first museums that I visited and later volunteered. It was there that I drew a deep sense of pride in my community and African American heritage. My journey to becoming COO of the International African American Museum experience is one of providence fueled by my early exposure to the power of history to inspire. I was a history major at Hampton University. My senior thesis explored the connection between Hampton Institute and the Penn School. I attended Divinity School at Yale where I focused on the idea of “public social witness,” that so influenced much of my volunteerism as a youth. To that end, I started a nationwide college access program at Yale and moved to Wash. D.C. to get it off the ground after graduating. I graduated from University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s American Studies Program in 2018. The program provided a great foundation for my work given the opportunity to do fieldwork in the South Carolina Lowcountry and beyond, interrogate the international dimensions of African American identity and creative expression, and the invaluable training I received as a fellow at the Ackland Art Museum in Chapel Hill, N.C..

What is your personal relationship with the African American food and cultural history that thrives in Charleston?

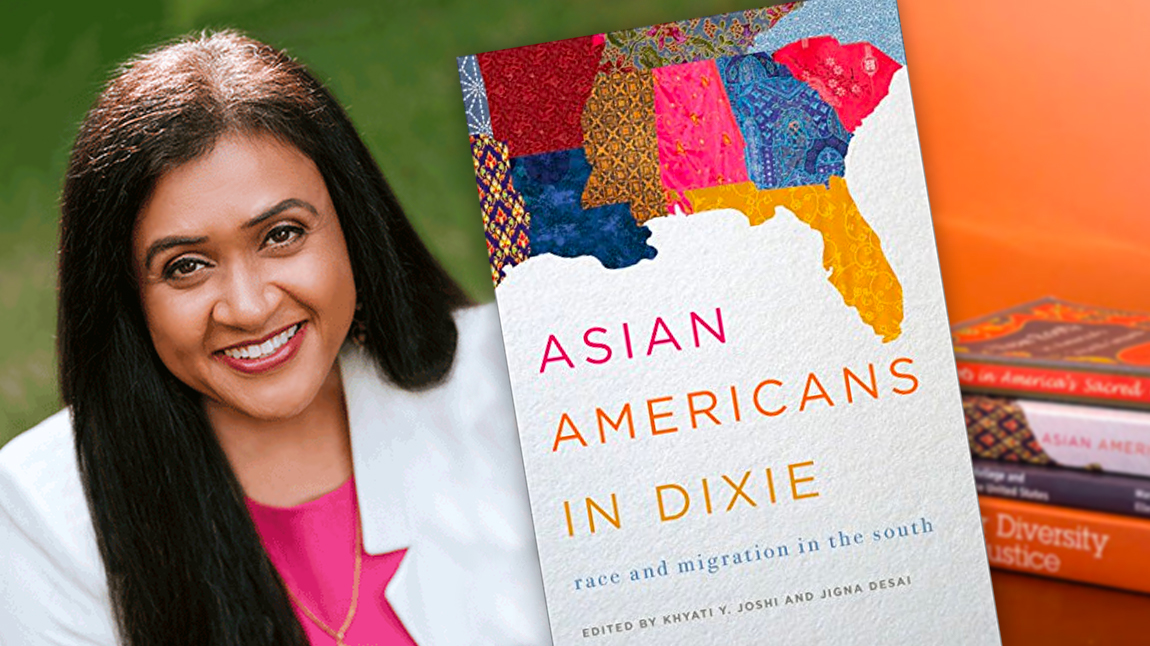

Professor Marcie Cohen Ferris introduced me to the notion of food as text, and the idea of "tasting your way through history." My own investigation of shrimp and grits — likely the most consistent breakfast dish in my life — revealed generations of traditions that continue to inform my life. My relationship with African American food and cultural history in Charleston is deeply personal. It is the significance of the table as a place to convene, gain nourishment, and traverse the inter-generational art of storytelling. It is the negotiation of legacy found in every recipe, cooking ritual, and meal. It is love. The love I felt from meals prepared by my late grandmother who dressed her table with linens and served food using her best china (if only for the two of us). Foodways reveal important details about the cultural nuances and practices that inform our American heritage.

What is the International African American Museum and why did it make its home in Charleston?

Charleston is the only place that the International African American Museum could be built because of the centrality of the city to African American history and culture. Nearly half of all enslaved Africans who entered America entered through Charleston. The future site of the museum honors this important history that we hope will become a sacred place of pilgrimage for all Americans. We argue that every African American can trace at least one relative to Charleston. It is because of this that Professor Henry Louis Gates refers to our site as “ground zero” for African American history.

What are some of the exhibits guests can anticipate seeing at the museum?

Our project is quite dynamic. It consists of our museum, memorial gardens, and a Center for Family History. The permanent exhibits will explore the African American journey through the lens of Charleston. It is a journey that begins in West Africa, intersects with Charleston as the single greatest point of entry for captive Africans in America, and beyond Charleston to impact the world. It is this impact that cannot be underscored. As with the story of Omar Ibn Said, that will soon be immortalized in an opera by Rhiannon Giddens, captive Africans were fully realized people forced into an inhumane system that did little to honor the complexity of their experiences. We will change that by not only honoring the many who died during the journey of the middle passage and on our future site, but by sharing untold stories of tragedy and triumph. There will be galleries exploring Gullah Geechee culture, the ingenuity required to cultivate rice and the resultant impact on the Charleston economy, the international dimensions of the African American journey, and the overall centrality of Charleston to American history. There will also be a changing exhibition gallery for the museum to create its own exhibits and host traveling exhibits.

How is the construction of the museum being funded? What’s the projected opening date?

The museum is funded by the support of our local and state governments as well as private philanthropy. We are projected to open in early 2022.

Will the museum include any memorials to Gullah Geechee culture?

Our museum will feature a gallery exploring Gullah Geechee culture. As a native, I am very excited about the space that we are dedicating to offering a comprehensive exploration of a culture that is deeply personal to me. Beyond the exhibition space, the memorial gardens designed by landscape architect Walter Hood will honor the many who arrived, the countless others who died at our site, and those who we lost during the Middle Passage.

When we were filming in Charleston, Vivian went on a carriage ride tour that talked about the rice trade and how the knowledge that enslaved Africans brought to America was pivotal to the emergence of Charleston as an economic powerhouse in the South at that time. Has that history somehow contributed to the construction of IAAM?

It is a central history. Consider that Charleston, South Carolina was once the wealthiest city in the colonies all as a result of rice. Rice is a staple of Gullah/Geechee cuisine and offers an important case study in the contributions of captive Africans to American society. It took a high level of expertise to engineer rice cultivation in the Lowcountry. I do not think we honor the skill and intellectualism of the individuals who literally built our city.

What new information will IAAM share about African American history?

It is easy to take for granted that there is an awareness of the true impact of the period of slavery on America and the African American community. There is still so much to learn. We will uncover these truths, offer a space to mourn the horrific conditions that have a lasting impact, and consider how we can effect change as a society. There is this idea that was introduced to me when I joined the team of “building bridges of understanding.” I see this as a key component of our work. I also think that an important aim of our work is representation. It is important to share the beauty and dynamism of the African identity that shapes so much of the African American cultural experience. It is also important to lean into the triumph bred through tenacity, innovation, and the creative spirit. How do we offer a community that has not been given a viable platform on the historic stage a platform to see themselves as agents in the American narrative? I am excited for both my grandmother and my future children to visit the museum and feel inspired by representations of their shared experience: the harsh truths but also the perseverance that affirms the legacy that we all are living into.

In our episode about porridge, we talk about soul food and ask a roundtable of African American food luminaries, chefs, and scholars: "What does soul food mean to you?” I'd like to pose that question to you as well. What does soul food mean to you?

It’s funny. I often joke that I only eat soul food at my grandmother’s table. What is fascinating is that what we have come to know as “soul food” is not monolithic. There is an approach to cuisine that is informed by my Gullah Geechee roots, and grandmothers even approached this very differently. I would hate to reduce “soul food” to any commercial representation of African American cultural identity. Vivian’s series does such a good job of complicating this idea. For me, soul food is about love. I do not cook, but my job growing up and even to this day is setting the table and cleaning up. My time in the kitchen is usually spent taking directions from my grandmother, mother, or aunts. Looking back, there are so many lessons to be gleaned from those experiences. The women in my family prepared most of the meals (my father only cooked breakfast) and they approached the meals and presentation with so much care. To me, the table is so key. My fondest memories are of my entire extended family: grandparents, parents, siblings, aunts. Cousins gathered around tables, together, engaging in a shared culinary experience. I think one of the greatest expressions of love is a cooked meal and I am fortunate to have had several throughout my lifetime. Some might say the cuisine was soul food, but I prefer to honor the gesture as being one from the soul.